Flyboy (Seeing is Believing)

The Dollar Savings & Trust Building.

Ever since the first-grade, Mom and I would make a regular trip to the city and the tall Dollar Bank Building where Dr. Peabody, Ophthalmologist, would examine the eyes of a little boy who didn’t see well. On this morning, Mom had already called the school principal to excuse me from my classes. Before long, we had parked the car in the big lot downtown and were crossing Market Street on foot to the sidewalk that led up to the building’s stout revolving doors. Mom helped me push.

The building’s elevator was old. When its massive gates parted to let us in, a small woman was revealed sitting on a maroon vinyl seat attached to the elevator. “What floor?” she asked, as we stepped inside. Sometimes Mom would try to hold my hand, but it was 1967 — and I was too old for that. I marched on with the confidence of all the boys in the second grade at Tod Woods Elementary School. Mom said, “Eleven, please.”

Our journey upward began with the sound of giant electric motors coming to life and a lot of clicking.

The elevator-lady sat perfectly erect, eyes forward, staring at the brass panel in front of her. As Mom and I stood at the back wall, the lady’s chubby arms cranked some mechanical levers to close the doors. Our journey upward began with the sound of giant electric motors coming to life and a lot of clicking. It was a slow, polite trip. Mom put her left hand on my shoulder as her right hand held her stomach. I stood with hands in pockets — taking them out once in a while to adjust the thick plastic frames of my eyeglasses. Sometimes on elevators, they slid down a bit.

Everyone spoke in hushed voices in the doctor’s office. Mom whispered my name to the receptionist. I found a seat and the latest Highlights magazine and got busy looking for the hidden pictures in the full-page drawing that was in every issue. Soon we were led to a long darkened room with a scientific-looking chair. Cabinets of drawers held little round lenses stored in wooden cases lined with dark green velvet cloth.

All about the room, shiny metal apparatus were neatly organized in proper places. Dr. Peabody appeared in the doorway wearing his white lab-coat, and as he greeted Mom, I stared at his big round hairless head. I was already seated in the scientific chair with my legs sticking straight out. As he approached, his familiar face became visible. With one of his large hands resting on my knee he asked in a smooth, concerned voice how I was doing this morning. “Fine, thank you,” I said. And the examination of my eyes proceeded with a thoughtful deliberation.

Eyechart

An illuminated chart was projected onto the darkened wall at the far end, and I was asked which letters I could read while looking through a black and silver mechanical mask with dial-up lenses. Mom sat on a stiff wooden chair in the shadows by the door. Dr. Peabody always put drops in my eyes to dilate my pupils. This made it necessary, upon leaving, for me to wear thin brown plastic wrap-around sunglasses with white flat cardboard arms fitted underneath my regular glasses. Walking back to the car after one exam, I peeked around the brown edges of the sunglasses. The city outside was a glowing white place with an orchestra of moving shapes and sound in the place of traffic, and glinting streaks of spectacular luminescent color that, were it not for the ache in my eyes, could have been a glimpse of heaven.

Dr. Peabody interrupted, “Better now, or worse?” As he changed the lenses in front of me, “Is one better or two?” As usual, I struggled to see even the medium-size letters. In the gaps of silence when I was trying to guess a letter, I often looked sideways at Mom to see the shape of her head turn toward the chart and then to me in the chair.

She could see the letters and wanted me to get them right. She was always hopeful. The end of this exam was different than the others. Dr. Peabody walked over to Mom and rubbed the back of his neck while he stood talking in a low voice. It was like the muffled kitchen voices of parents transmitted through the floor of an upstairs bedroom late at night. My eyesight may have been poor, but my hearing wasn’t. I overheard several of the clipped sentences. “There is no improvement . . . if . . . continues. . . he will be blind by the time he is 21.” Mom sat back down in the hard chair. Dr. Peabody came back to me and told me I had a “lazy eye” and I would need to wear a patch over my good right eye for a while to try to make my left eye stronger.

We didn’t go straight home after the exam. Instead, Mom took me to Woolworth’s for a milkshake. We sat at the department store’s lunch counter and I tried not to look conspicuous with my bandaged right eye, thin brown sunglasses, and my glasses on my head all at the same time. I sure did not want to go back to school, but I knew I would. We stopped at home first, and Mom made a phone call while I looked at myself in the bathroom mirror. I never told Mom what I heard at the doctor’s office. And she never told me. On many of the nights that followed, I would get out of bed in the dark and walk around with my eyes closed to practice for when I would be blind.

I think some of the kids thought the bandage was there to hold in my eyeball after some terrible accident.

As expected, my arrival at school was dire. We met my teacher, Miss Adams, outside my classroom. There was a little talk, and then Mom said goodbye. Miss Adams asked me to wait outside the room for a moment as she disappeared behind the door. The kids saw me standing there in the time of the door briefly swinging open and shut again. Miss Adams reappeared and led me into the classroom past the two long art tables and Lilliputian desk-chairs containing my classmates.

The kids pretended hard to not pay me too much attention as they were instructed. But before long, all were staring, and Miss Adams explained my predicament in a few short sentences. I think some of the kids thought the bandage was there to hold in my eyeball after some terrible accident.

On the playground, my pal, Chuckie Arquilla confided that his brother knew someone with a wooden eye. Chuckie bet it could be taken out and rolled around like one of our marbles. When the bell rang, I took my seat next to the slow kid, Dave Clark. Dave had a butch haircut and a metal plate in his head. If you looked closely, you could see where the stitches had healed around it on his scalp. We must have been a rare sight sitting there together — Cyclops and Miniature Frankenstein of the second grade. I imagined the pair of us lurching around in shredded clothes at recess, zombie-like, as the other kids shrieked and bolted from our path. Soon we’d live under the old cement bridge at the edge of town and survive on river water and scraps of food thrown at us by kids during their escapes from our terror.

Miss Adams immersed us in the day’s lessons and the kids’ stares eventually tapered off. Dave looked at me for a long moment. Then he slipped out a half-completed drawing of one of his fantastic rocket-cars and meticulously began to add flames shooting out from the back tires without ever looking at me again.

I used to draw airplanes. I used to think about my little face framed in the windshield of airplanes overhead. Me, looking up at me — looking down on me.

For a while, I was promoted from the ungainly white eye bandage to a sleek oval flesh-colored sticky-patch. Long after the elementary school years and countless eye exams, everyone adopted a wait-and-see attitude concerning my sight. Nothing was ever said.

As a sophomore in college, I still dreamed of flying an airplane. It wasn’t an obsessive calling to the wild blue yonder like in the books. It was more a quiet longing like I never knew before. It wouldn’t wash away, and it would not heal. I discovered through reading books about pilots that they all had eagle-vision. “Twenty-twenty,” it was called. I didn’t actually know the acuity of my own eyesight. I reckoned my vision wasn’t really measurable by modern science, so they just gave me the thickest lenses they had.

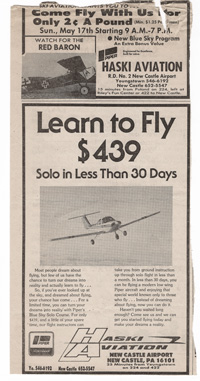

What I didn’t know, was that the Federal Aviation Administration required a pilot’s corrected vision be at least 20/30 in each eye to be considered for the private pilot license. A skinny flight instructor named Marty Haski told me this as I stood in his small office at the New Castle airport in Pennsylvania in October of 1980. In my left hand was a wrinkled advertisement torn from the local newspaper that described, “Piper’s Blue Sky Solo Program.” “Solo in 30 days for only $439.” The fine print said this price was for, “Up to 12 hours flying over 30 consecutive days.” I found out later that the private-pilot course would require a minimum of 40 flight-hours and successful completion of written, oral, medical, and practical flight exams to get licensed.

The medical exam came first and I discovered my corrected vision was close to the minimum requirements. I wasn’t thinking about exams when I took out a small loan that Mom co-signed to cover the additional costs of training. She said if Dad had lived longer, he wouldn’t have believed it. I didn’t tell anyone about my trips across the Ohio border to the little Pennsylvania airfield. I had a small social-security supplement from when Dad died to help me through college and it would be discontinued when I was 21 — this year. I wasn’t blind yet. Working several part-time jobs paid for books and the new monthly payment to the bank for flight training.

I flew solo on a cold gray December morning in 1981. Marty and I had been flying for 45 minutes and he was critical of my efforts in the cockpit. He was persistent about maintaining correct airspeed and adding a notch of flaps on the base and final legs of the approach to landing. Did I, “See the snow and ice” on the east end of the runway and the “Beech Baron entering the traffic pattern downwind behind me?”

On the last landing of the morning’s practice we taxied back to the hanger and before I could shut down the engine, Marty reached up to the overhead latch on the canopy, opened the door, and stepped out onto the wing of the airplane. He shouted into the open door, “Make three more good landings and park the airplane by the pumps when you get back.” “Be careful,” he said.

Certified Flight Instructors. Marty Haski 2nd from left, his father Joe Haski 2nd from right.

He shut the door and I was on my own. It was a long time before I understood the awesome responsibility that this skinny man from Pennsylvania had stuck to his bones. He never looked back as I taxied to the runway to make three landings. My first departure alone was accompanied by a lot of excited yelling — my own. The exhilaration quickly subsided as I tried to think about what to do next without the comfort of Marty’s experience in the right seat.

Once on a hot summer departure from the shorter runway at New Castle, the airplane climbed too slowly to clear the tall stand of trees at the rapidly approaching opposite end. Marty pushed the stick forward and we quickly gained speed and necessary altitude. The wheel struts snatched some branches from the canopy of the trees as we flew over. Marty muttered something about surprising the owl that lived in the tree. I learned that flight instructors occasionally could earn their entire hourly rate in less than a minute.

I never skidded sideways in an airplane before and I didn’t want to crash.

My first landing alone was uneventful. On the second, the airplane touched down on a patch of ice and started to skid sideways off the runway. I never skidded sideways in an airplane before and I didn’t want to crash. Full throttle and quick back-pressure on the stick eliminated the problem and I flew away from the danger thinking more like a pilot. The third landing ended with a handshake from Marty and a joyous, weary ride back home alone across the state line to Ohio in my car.

A while later, I passed the written exam. Then came eight months more of flying, ground instruction, simulator training and solo cross-country flights on the way to the oral exam and flight-test. I flew at night. I flew with Marty’s father, Joe Haski, who put the airplane into a spin that I had to fly out of safely. Some pilots told me later he was crazy for spinning the small T-tail trainer because the characteristics of the design made spin recovery difficult.

I never doubted that we would fly out of the spin. And I never once thought Joe Haski was crazy. As the airplane turned its way around toward the ground, he talked carefully to me about how to deal with the problem — it was the most he had ever said in months of regular visits to his airfield. This was a gift. I felt I must have been getting close to the time when I would take the flight test.

By mid-August I was ready. But unlike the other students, I wasn’t going to get a flight with the FAA flight examiner who worked out of the field where I practiced. Marty told me to operate as pilot-in-command, I would need a Demonstrated Ability Waiver attachment to my flight medical certificate. I had almost forgotten about my eyes. Attempting to get this waiver would require me to fly to the much larger Allegheny County airport near Pittsburgh to take the test with a special examiner at the Flight Standards District Office on the field. I had confidence in the abilities Marty had developed in me, but even he could not help me to see. I felt my flying would soon end with this last test.

The day arrived and I set out early from the small airport in New Castle on the 55-mile flight southeast to Allegheny. The flight would take me over a fragment of the rolling Allegheny Mountains and the crooked trace of the Monongahela, Allegheny and Ohio rivers flowing together where the city of Pittsburgh grew. The sun was still low in the morning sky and the banks of the rivers were rounded in shadow. The water was dark green and gold with sun, fading to black at the rim of earth that shaped its flow. The contours of farm fields were unveiled in the brief morning light and would not appear again until sunset.

I slipped below the outer ring of Pittsburgh International Airport’s terminal control airspace. This slice of atmosphere began at 4,000 feet, continued up to 8,000 feet and extended 25 miles in all directions from the center of the place where real pilots made a living flying passengers and freight to destinations all over the world. The Boeing 747 passing thousands of feet above my little two-seat rented Piper Tomahawk was heading for one of the two-mile long concrete runways at Pittsburgh. Its pilot and crew were scarcely aware of me, or my effort to maintain a course to Allegheny to meet a stranger who would decide if I had sense and skill enough to occupy the sky alone in a thing with wings.

God gives wings to insects and birds, fish and angels.

A pilot’s license has no expiration date — but a medical certificate does — and this document is devoutly governed by the FAA’s Aeromedical Branch and the peculiar limitations of a human body and mind. God gives wings to insects and birds, fish and angels. Everyone else must apply to the FAA.

Attaching wings to a person on earth requires navigating a regulatory labyrinth designed to protect other inhabitants of the planet as much as the fledgling pilot from himself. An individual’s reward for coming out the other side deserves nothing less than wings for life. Look into the eyes of an old pilot and you will see a deep gratitude for the privilege of being left alone to the sky.

Allegheny County Airport, West Mifflin, Pennsylvania.

In an office next to the Flight-Service Station on the second floor of the terminal building at Allegheny, I met the man to whom I would pay $65 to scrutinize my every thought and motion in an airplane. The examiner extended his hand to greet me, but I couldn’t do the same.

Freeing up my shaking hand required me to wedge underneath my left arm a sectional chart, IFR-hood, pilot logbook with Marty’s endorsement to take the flight test, and a navigational plotter. Transferring my E6B slide-rule flight computer and a couple pencils to my left hand took an extra few awkward moments. He waited patiently with his arm out like a tree limb.

He was professional, not particularly chatty. He seemed 20 years older than me, was clean-cut, and he had on a short-sleeve yellow shirt over a white undershirt. His arms were thick, I guessed maybe from playing ball in college or flying bombers in Vietnam. I was sure he had not always pushed a pencil to make a living. He was a career pilot, probably with more ratings and flying hours than I would ever know in my lifetime. He possessed a civil suspicion, not unlike the kind owned by the father of a girl you wanted to ask to the dance. We spent 30 or 40 minutes talking about FAA regulations, airspace restrictions, medical certificates, weather minimums, navigation, aircraft weight and balance, emergency procedures and other areas of fascination to would-be pilots.

The office seemed air-conditioned when I entered. I think the examiner shut it off.

Actually, it was I who did most of the talking — and sweating. The office seemed air-conditioned when I entered. I think the examiner shut it off. He appeared satisfied with my responses because he stood up suddenly, and told me I should only need 10 or 15 minutes to plot a course to Morgantown, West Virginia. “Oh, and by the way,” tell him when I was ready to meet him on the ramp — he wanted to watch me pre-flight the airplane. He left me sitting at the long table. I watched him walk over to his desk where he sat down and began to read the newspaper.

The oral part of the exam was over. I scoured my sectional-chart for Morgantown, flipping it over a few times without finding it. The examiner looked up once and we made eye contact for a microsecond. My heart was racing. I thought I was taking too long to prepare for our flight. In this same instant, I realized I had no hope of finding Morgantown – because it wasn’t on my navigational chart.

The Morgantown he wanted me to fly us to, was too far south to be depicted on the only chart I brought for the exam. I had heard of students being failed for arriving to the flight test unprepared. I thought I’d be the next. With nothing to lose, I approached him and asked for a Cincinnati sectional chart that picked-up where mine left off. He looked at me without saying a word and produced one from the top drawer of his desk. I felt relieved. I went back to my table to plan the flight, and he disappeared. I quickly and carefully as possible plotted a course, taking note of estimated time enroute, fuel required, and the radio frequencies, traffic pattern altitude and runway length at our destination.

All that was left was to check the local weather forecast for Morgantown. When I did, my heart sank. Flight Service was reporting three miles visibility in fog and an overcast layer at 2,800 feet. To fly into this weather would be foolish for a novice pilot. I thought for a long time about what I should do. I told the examiner that I didn’t feel too good about taking us to Morgantown. I actually thought he would be surprised that the weather was bad and he would certainly suggest another destination.

He studied me again for a moment and said, “We’re not really going all the way to Morgantown.” Like I knew this all along. “Just get us established on course and I’ll let you know what I want you do next.” After scrupulously pre-flighting the airplane under his watchful eye, we departed runway 31 at Allegheny and I contacted the departure-controller on the radio to confirm our course heading to Morgantown. My examiner spoke even less than old Joe Haski.

When his voice did find the occasion to rise above the roar of the engine, it never failed to command my immediate attention. His words were always spent in the form of a question. “Where would you land if you lost an engine now?” This preceded him throttling the engine to an idle to simulate a loss of power. “What transponder code would you use in a radio failure?” “What code should you never use?” “How far are we from the Johnstown VORTAC?” I flew at minimum controllable airspeed, I demonstrated 45° and 60° steep turns, accelerated aerodynamic stalls – in short, everything Marty had taught me to expect, with a few minor personality twists and subtleties due of the examiner.

On the return to Allegheny, “Show me where we are on the chart.” “What is the field elevation of the airport we just flew over?” “Do you see the traffic at 11 o’clock, about two or three miles at 3,000 feet?” This was the question. Simple enough. Direct. Matter-of-fact, as all of the others had been. He had just asked me if I saw another airplane flying in the sky with us. An airplane that, were it not for a slight difference in altitude, could easily present a collision threat if I could not identify it and maintain a safe distance. Several of his earlier questions, I think, must have determined I could see the obscure symbols on the navigation charts while we were flying and also interpret the calibrated markings and read-outs of various flight instruments.

Now, he was curious about my distance vision. I scanned the area where he reported the airplane. At that distance, an airplane with a wingspan the length of an ocean yacht is reduced to a moving speck of light-colored metal against the terrain below. I had little hope that it was an American 727 on its way to Pittsburgh — as if an airliner might actually dare to fly so low 20 or more miles away from its intended runway. In desperation, I told him about the Cessna off our right wingtip that was probably in the traffic pattern for landing at Rostraver airport. And, “A moment ago,” we passed over what looked to be another Cessna doing some sightseeing at a bend in the Allegheny River.

But neither of these airplanes endangered our flight path and they weren’t the airplane he asked me to confirm. “Still looking. . .,” I told the examiner. I looked for as long as I could before contacting approach-control and entering the traffic pattern for our landing back at Allegheny. I never saw the airplane. I landed a little long and fast, missing the first turn-off on runway 31, so the taxi back to the terminal was not brief. Little was said. He shuffled some papers and wrote a few notes.

I thought about what I had just done. And how it felt. Hearing the roar of the engine in flight. Feeling the sweat on the back of my shirt. My strain to meet so many expectations. Turning, climbing, floating almost weightless in one moment, and in the next, pressed into the seat at twice my weight on earth. So this was flying. I have been lucky to know this much.

August 31, 1981. Polaroid from CFI's notebook.

At times I worked against the mechanical — the physics of the thing. I was learning to shape letters in the air with an awkward implement, but with words I already knew in my heart. The art of the thing — like penmanship — is scarce in these times. It is the grammar and parsing of thought that is so important. Yet, the promise of that perfect arch and rise and descent of stroke on both paper and sky speaks to the patient and watchful.

I flew home alone. A small speck, in all sky. Three hours and six minutes over a quilt of Pennsylvania earth and rivers. It does not seem possible that time could move beyond that moment.

As I look out now, from my bedroom window and gaze upon that memory of a young man with new wings, I see him as clearly in my mind as if painted on the glass in front of my face.

Tonight, as my wife and children sleep, I will practice once more — this time, with pupils wide and a memory searching among familiar stars and clouds. I have seen the world from above, and can look upon it with new awe — and the grateful eyes of an old pilot.

.

.

N9313T Piper Tomahawk.

.

.

It is a long way from New Castle Pennslvania, but N9313T, the 1978 Piper Tomahawk PA38-112 Murray learned to fly in — is still teaching students. We found it at Aviation Pacific’s flight school in Oxnard, California.

Hey thats the A/C which i flew! I’ll never forget, first time i flew this a/c I had an actual comm. failure…

Hi Nikit,

Amazing. Small world eh? It was a lot newer when I flew it!

Amazing Indeed!!! It still remains one of the better Tomahawks which I flew…last time I saw N9313T was 2 years ago and it still looks just like the one in the picture..

You should consider sending us a story? Check out “Send Us Your Best” above…